Regaining America's Balance

The history of the rise and fall of powerful nations offers a lesson that Americans today must not ignore: Great powers are rarely brought down by outside adversaries; they destroy themselves from within. Very often, they do it by falling victim to economic imbalances and the decay of once-vibrant governing institutions that prove unable to adapt to changing circumstances.

The pattern has repeated itself with remarkable regularity. In examples as disparate as the demise of the Roman Empire, the decline of imperial Spain, the fall of the Ottoman Empire, and Britain's loss of global power, we find a common story: As political institutions fail to keep up with economic changes, elites respond by concentrating political power, increasing public spending, and eventually taking on an unbearable burden of debt that brings down the entire system. If America's global economic power comes to an end in our lifetime, it will surely result from a loss of fiscal balance that forces the nation down this well-worn path. The subtle signals we have already received — a minor credit warning from Moody's, acrimonious political fights over the debt ceiling — confirm that trouble is coming.

Indeed, it is now perfectly clear that our political system is struggling to contend with an economic and fiscal reality for which it was not designed. That reality is above all a function of our ballooning entitlements and of the peculiar political incentives and forces that have grown up around those entitlements. The structure and rules of our politics create a situation in which it is in the interest of both major parties to let these problems get worse rather than to take the steps required to address them.

This is a depressing fact, but it also suggests the shape of a solution. If we are to prevent the entitlement state from leading us into a fiscal catastrophe, we will need to change the rules of our fiscal politics — especially the rules of federal budgeting.

THE GREAT IMBALANCE

America today faces a financial imbalance that threatens our economic strength and position of global leadership. At its core, the threat is a function of a breakdown in long-term fiscal discipline. Under President Obama, the budget deficit has grown to more than $1 trillion every year, with more than $3 trillion in expenditures funded by about $2 trillion in tax revenues and the remainder by debt. That deficit now amounts to more than 7% of our annual gross domestic product, and the consensus is that such spending is not sustainable. Indeed, the only reason the United States has gotten away with funding a runaway national debt at relatively low interest rates is that some key competitors, especially in Europe, are in even greater fiscal trouble.

While this problem has drawn much public attention over the past four years, it has been far longer in the making. To be sure, the Obama administration has worsened the nation's fiscal situation. But the country faces longer-term structural budget problems that have been growing for decades — problems that our federal budget process has simply failed to address.

Politicians like to focus on federal discretionary spending when they talk about those budget troubles, because discretionary spending presents some relatively easy targets for cutting. Many on the right argue that reducing foreign aid or subsidies to public broadcasting will meaningfully help our budget situation; many on the left claim that cutting tax breaks to corporations or slashing the defense budget can save us. But they are all wrong. The growth in our debt is not being driven by these comparatively small programs.

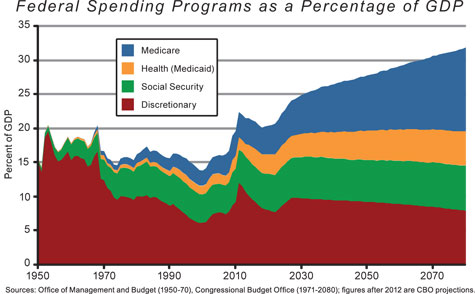

What we are facing is an entitlement crisis. It has been growing for decades, and it is reaching a truly catastrophic scale. Consider that four decades ago, in 1973, the federal government spent 17.6% of the nation's GDP. Of that amount, 3.7% of GDP went to Social Security spending, 1.1% was for health-entitlement spending (Medicare and Medicaid), and 9.9% was discretionary spending (including defense), according to the Congressional Budget Office. In contrast, the federal government in 2013 is projected to spend 21% of the nation's GDP, not counting interest. Of that spending, 5.1% of GDP will go to Social Security, 5.6% will be health-entitlement spending, and 7.8% will be discretionary spending. This means that, as a percentage of the economy, federal discretionary spending has actually declined over the past 40 years while entitlement spending (especially health-entitlement spending) has increased dramatically. And the CBO projects that this pattern will continue in the coming decades.

On this much, nearly everyone agrees. But there is no similar agreement about how to bridge the fiscal gap. And the difference on that front is not so much between liberals and conservatives as between those who seek the right mathematical formula and those who seek the right budgeting rules.

Recent years have seen several proposals to close the fiscal gap. Some of these plans have been part of the formal budget process, like the House Republican budgets of the past few years. Some have come from government efforts, like the Simpson-Bowles commission created in 2010 by President Obama. Others have come from private sources, like the Bipartisan Policy Center's Domenici-Rivlin task force. There have been dozens of similar plans proposed since the early 1980s, when Ronald Reagan put a spotlight on the coming federal fiscal imbalance. Many of these proposals would likely have addressed the basic problem, but none of them has been enacted. This should suggest that the problem is not that we lack a plan with just the right mix of policies, but rather that we lack a process by which a viable solution could actually become law. Put simply, our runaway budget deficits are not a math problem. They are fundamentally a political problem.

Some in Washington do seem to recognize the true nature of the challenge they face. Perhaps the most significant recent effort to address the fiscal imbalance was the creation of a congressional "supercommittee" in the course of the 2011 debt-ceiling deal between Congress and the president. The supercommittee — formally known as the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction — consisted of 12 members of Congress (three members from each party in each chamber) and was charged with developing a plan to reduce the deficit by at least $1.5 trillion over ten years. Its recommendations were granted an exemption from the usual rules of debate in both houses of Congress: They would have been given a straightforward up-or-down vote, without amendment and without the possibility of a Senate filibuster.

The supercommittee failed. A few days before the group was required to announce its recommendations, the members instead announced that they had reached an impasse. But the very fact that the committee was created — that the president and congressional leaders acknowledged that addressing our fiscal imbalance required changing the rules of the legislative process — was an important step forward. It offered reason to hope that the nation's leaders finally understand why our fiscal woes have gone unaddressed: not because of a failure to find the right budget formula, but because of a failure of governance.

When politicians and journalists acknowledge that problem, however, they usually do so in the context of criticizing American democracy itself, or of complaining that there are just too many obstacles to enacting legislation. But that critique is not quite right. After all, even as our mounting fiscal crisis has gone unaddressed in recent years, Congress has nevertheless managed to pass a great deal of major legislation. During the terms of George W. Bush and Barack Obama, politicians in Washington have enacted, among other laws, a large education reform, a huge re-organization of our domestic-security agencies, a reform of corporate-governance rules, a new Medicare benefit, a massive response to the financial crisis (including several stimulus bills, an unprecedented bank rescue, and a bailout of auto companies), a huge health-care reform, and a major overhaul of our financial regulations. The system we have, in other words, can do a lot. It is well designed to balance interests, to channel public desires, to focus political energy, and to enable responsive government.

But there is one big thing it cannot do: It cannot govern the entitlement state. A system that worked well for two centuries is now failing precisely because it is being asked to run a fundamentally different type of government — one that exists largely to provide material benefits to individuals. This is where the source of our dilemma lies, and it is where any new budget rules must be focused.

GOVERNING THE ENTITLEMENT STATE

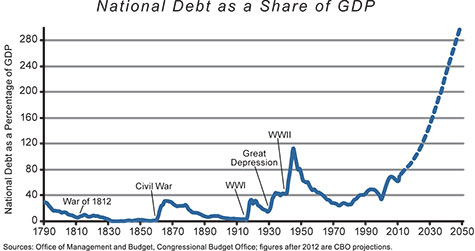

The unprecedented nature of the problem confronting policymakers is readily illustrated by a look at America's debt. The figure below traces the national debt as a percentage of GDP since 1790. It demonstrates that, until about the 1970s, our debt spiked only during wartime (and the grave economic catastrophe of the Great Depression) and tended to decline or to hover at very low rates in peacetime. The spikes on the chart conform plainly to the War of 1812, the Civil War, and the two world wars, with an additional spike in the early 1930s resulting from government spending to combat the Depression.

But the spike in borrowing and debt that began in the 1970s and persists to this day is not explainable with reference to any external shock or economic calamity. It has continued almost unabated through good economic times and bad. According to the Congressional Budget Office, it will continue to grow far worse in the coming years — eclipsing even the enormous debt spike during the Second World War.

What is the crisis that explains this extended period of intense borrowing? It is the crisis of the welfare state. In the United States, the introduction of Medicare in 1965 and structural reforms to Social Security in 1972 bound the federal government to significant expenditures extending into the distant future, beyond the horizon of political consequences. This created the political dynamic that has enabled unprecedented spending — yielding a four-decade period of growing fiscal imbalance that is now becoming truly disastrous.

The catastrophe has been building slowly. When Social Security was signed into law early in Franklin Roosevelt's presidency, it was a modest program to fight destitution among the elderly, and it worked. No longer do we see many senior citizens who are homeless on the streets. And the income supplement was relatively small: The first monthly payment, to retiree Ida Fuller in 1940, was in the amount of $22.54.

Today, however, Social Security is a major retirement pension, with average payouts of more than $1,200 per beneficiary per month. Demographics are driving the system toward bankruptcy. More than 50 million people, one-sixth of the population, receive Social Security checks. This number is much larger than the system's designers anticipated, and the increasing longevity of retirees is accelerating the program's fiscal decline. Moreover, roughly one-fifth of recipients are not even retirees: They qualify under Social Security's disability benefit, which has grown far more dramatically than trends in observed workplace disability.

The fiscal consequences of these trends are dire. Social Security's trustees reported in 2012 that the so-called "trust funds" through which the program is financed — basically accounting conventions that theoretically set aside payroll-tax dollars for Social Security while actually spending the money on other programs — will be empty in 2033.

The structural problems are even deeper for Medicare and Medicaid. Medicare provides health insurance for roughly 50 million Americans, mostly over the age of 65. Medicaid is a joint federal-state program that offers similar insurance to low-income people and now supports more than 60 million beneficiaries. Unlike Social Security — which simply transfers cash from the young to the old — these programs provide a service that is itself getting more expensive, in no small part because of these ill-designed entitlement structures. Both programs displace private health insurance; they also generate perverse incentives within the insurance market by shielding consumers from costs and providers from real prices. Medicare recipients can demand substantial medical care without ever having to pay the bills, leading to overconsumption and needlessly rising demand for care. That explains the spiraling costs, but it's not the entire story. As the late Milton Friedman explained in 2001, this dynamic also hurts patients by elevating the bureaucracy over doctors in the course of rationing care.

What these three programs together illustrate is a failure by policy-makers to think ahead. Over the decades, elected officials promised increased future benefits to reap immediate political payoffs. The real costs of these entitlements were placed safely beyond the politicians' career horizons; even today, lawmakers who seek to reform the entitlement state face severe political consequences. The bill for this reckless, unsustainable behavior is coming due, and yet the political incentives all still encourage policymakers to abide a perfectly avoidable fiscal catastrophe.

Why do the normal political motivations and institutional mechanisms of our constitutional system not enable a solution to this obvious fiscal imbalance? To grasp the answer, we must begin by recognizing that our politicians are acting rationally. And to illustrate the point, we can look at a famous example from game theory: the prisoners' dilemma.

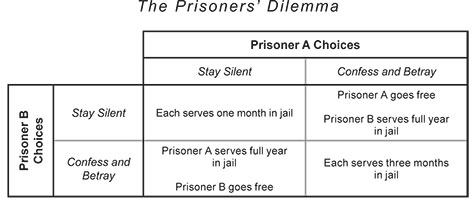

Originating in the work of RAND Corporation scholars in the 1950s, the prisoners' dilemma gets its name from a thought experiment involving two suspects arrested and questioned by the police regarding a crime they are accused of having committed together. Lacking much evidence, the police separate the suspects and present both of them with the same offer: If neither suspect confesses, both serve one month in jail. If both suspects confess, they both serve three months in jail. But if one suspect confesses and agrees to testify against his partner while the other does not, the betraying suspect will go free while the betrayed suspect receives the full one-year sentence. What should the prisoners do?

At first, it seems irrational for either to confess. After all, if both hold firm, both will serve short sentences. But when one considers all the potential outcomes of their situation, and assumes that each prisoner's prime concern is reducing his own punishment, it turns out that each prisoner is actually better off confessing and betraying the other — regardless of what the other prisoner chooses to do.

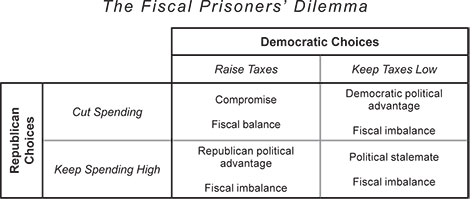

American politics today is presented with a similar dilemma. There are two paths toward reducing deficits and debts of the magnitude we face: raising taxes or cutting spending. A balanced compromise would involve some amount of both, but the two political parties face strong electoral incentives to do neither. If Republicans push for reduced spending, they are criticized for taking away the benefits people rely on. If Democrats push for raising taxes, they are decried for swiping workers' hard-earned dollars. Both solutions are seen as taking money away from voters, and are thus fraught with political peril.

Consider the matrix above, in which both Republicans and Democrats in Congress have two policy choices. Republicans always promise lower taxes, so their choice is whether to cut or maintain spending levels. Democrats, in contrast, want to keep spending high, so their choice is whether to raise taxes or keep them low.

A close look at the matrix shows that it is politically rational for the Republicans to maintain today's unsustainable levels of spending when faced with either behavior from Democrats. And, campaign rhetoric aside, that is what they tend to do. Republicans have learned that whenever they actually legislate spending cuts, they are attacked by their opponents and tend to lose elections. They are not keen to do the fiscally responsible thing when the price is giving up power.

Likewise, whether Republicans cut or maintain spending, Democrats are politically better off if they allow taxes to stay low. This explains why, despite President Obama's rhetoric about raising taxes, he and other Democrats have generally refrained from actually doing so, especially at the levels needed to pay for their spending. That the expiration of the Bush tax cuts was postponed until after the 2012 election was not a coincidence.

To be sure, politicians in both parties make noises about good economic choices (from their perspectives) that balance the budget, but their actual behavior is what matters. President George W. Bush oversaw the expansion of spending on entitlements, as well as on defense, education, and other discretionary programs. President Obama serially preserved Bush's tax cuts. Politicians know what is best for the country in the long term, but they have no easy way to change their behavior now during a period of polarization in which the institutions and incentives are set up for imbalance.

This amounts to an institutional failure. For most of the nation's history, the rules of the budget game worked. Today, however, they no longer function. Politically rational behavior is now fiscally perverse. Addressing this institutional failure thus requires changing the rules of game. The only remedy to our political prisoners' dilemma, therefore, is to change those rules so that they in fact rule out structural fiscal imbalance — by imposing painful penalties on lawmakers for failing to budget responsibly.

CHANGING THE RULES

Legislative efforts to rule out fiscal imbalance have been tried before, but have proved too weak to succeed. Given this track record, it is worth briefly examining these attempts to learn what not to do when designing new rules for the budgeting game.

The earliest efforts were the so-called "Gramm-Rudman-Hollings" budget rules, enacted through two statutes, the first in 1985 and the second (after a partially successful Supreme Court challenge) in 1987. These rules established caps on federal spending, enforced through automatic cuts — called sequestration cuts — that would take effect when the caps were breached. The caps were based on fixed deficit targets, but those lasted only a few years, as Congress found them too difficult to abide by.

They were replaced in 1990 with "pay as you go," or PAYGO, budgeting rules. Under such requirements, every new dollar of spending must be funded directly by a new dollar of taxation or cuts to spending elsewhere. The idea was that Congress would essentially be unable to take on new borrowing, except in a few exempted categories. But by the late '90s, Congress had found creative ways around the rules; ultimately, the PAYGO system broke down and was allowed to expire in 2002. Aspects of the system have since been brought back, but these partial remedies, too, have proved thoroughly ineffective at restraining deficit spending.

These kinds of rule changes essentially tried to outlaw the logic of hyper-partisan budgeting in the age of the entitlement state. And they failed — not only because their various constraints were not binding, but also because they neglected to take account of why our policy-makers have not behaved responsibly. The basic dynamics of our politics are not going away; successful rule changes must therefore take account of those dynamics, rather than pretending they can be eliminated by fiat. Politicians need to face much more persuasive incentives to achieve fiscal balance.

Ultimately, implementing reforms to address our self-destructive fiscal habits will require Americans — and their representatives in both parties — to recognize the congressional prisoners' dilemma and agree to change the rules. This means that those new rules cannot be divisive: They cannot prescribe a particular policy of spending or tax changes as a remedy and expect that one-sided fix to be enough. Rather, they must focus on developing a budget process that is politically viable and that brings the country toward a lower and more stable debt-to-GDP ratio. Both Congress and the president will face greater disincentives to continue the fiscal imbalance if its true costs are made more visible and its consequences are made more immediately onerous. If we can break the prisoners' dilemma and fix the politics of our fiscal imbalance, the economics will take care of itself.

Four kinds of rule changes would advance this cause. First, Congress should change the rules that define how taxes and expenditures are "scored" for budgeting purposes by the Congressional Budget Office. Today, fiscal changes are modeled by CBO in static terms with no consideration of the effects of different policies on economic output. For instance, in providing Congress with an official estimate of the effects of a tax cut or increase, CBO does not try to estimate how the change would influence people's willingness to work long hours, and therefore influence their earnings potential. In another example, the extension of unemployment insurance to 99 weeks — adopted in stages over the past few years — is acknowledged by most economists to have caused higher unemployment rates. And yet these kinds of dynamic behavioral effects are not considered in CBO's macroeconomic modeling.

CBO should thus be required to offer estimates of dynamic effects using broadly accepted economics methods — whether as part of its standard scoring of legislation, or appended to such scores as additional budget scenarios. Moreover, the agency's semi-annual economic and budget projections should be required to include forecasts over long horizons. Today's artificial five- or ten-year horizons are easily manipulated by legislators eager to hide the costs of legislation in the more distant future; a budget window of several decades would allow for much more honest estimates. And CBO reports should include an accounting of entitlement programs' expected future liabilities and annual changes in accrued liabilities, not just current costs. That is, when costs or numbers of beneficiaries are expected to rise down the road, such changes should be acknowledged and accounted for now. As things are arranged today, Congress can feign ignorance when, year after year, the Social Security trustees issue their annual report announcing that the program is more costly than they had expected in the previous year's projection.

Second, Congress should fundamentally reform its budget process. For one thing, the budget passed by Congress each year should be an actual piece of legislation — not just a resolution — so that the president has to sign or veto it. If that change were implemented, the president would have to engage the details of the budget process seriously, rather than put on the irresponsible charade that now passes for an administration budget proposal. The budgets proposed by the Obama administration in recent years, for example, have garnered zero votes in the Senate.

Congress could also give real teeth to efforts to slow the growth of spending by changing the so-called "baseline rule" that automatically adjusts the starting point of the next budget cycle to reflect expected future increases in cost. The rule is effectively an automatic spending increase each year to keep up with inflation, population growth, and other variables. Eliminating baseline budgeting and instead writing a new budget from scratch each year would mean that all increases in discretionary spending would have to be scored as such, raising the visibility of spending increases to the public. It would also be wise to put all types of spending — mandatory "entitlements" as well as discretionary outlays — on equal footing and subject to an annual constraint, so that entitlements could no longer continue to grow automatically.

Third, Congress should formally set long-term targets for a well-defined debt-to-GDP ratio that includes both the explicit debt and the implicit liabilities in our entitlement programs. Explicit debts are those associated with outstanding government securities — money the government has actually borrowed in the open market. Implicit liabilities are, for the most part, future promises to pay Social Security and Medicare benefits minus expected future payroll taxes. For example, Americans apparently have the bad habit of living longer than the architects of Social Security expected. According to the program's trustees, changing demographics are the dominant reason why the Social Security trust funds were estimated in 2012 to be exhausted three years earlier than had been estimated in 2011. Failure to achieve newly established debt-to-GDP targets (with exceptions for serious economic downturns or major wars) would require congressional action — automatic pay cuts for federal workers, say, or across-the-board sequestration. Sequestration has, of course, failed before. But connected to the other budget-rule changes proposed here, it could enable the new budget process to be directed toward specific targets, and therefore make ad hoc revisions of the rules more politically difficult.

Finally, we should change the basic rules of the budgetary game to leave no room for entitlements to balloon while Congress stands by. One way to do so is through the passage of a realistic balanced-budget amendment to the Constitution. Recent attempts to pass such amendments have not involved particularly plausible versions of the idea: For example, the proposed amendments that nearly passed in the 1980s, in 1995, and in November 2011 involved requirements for "within year" balance. This means that federal expenditures in 2019 must equal revenues in 2019, a problematic constraint when tax revenues fluctuate with the business cycle, often by 10% or more. Abiding by that rule every year would push Congress to attempt to fine-tune the economy, and in ways that would inevitably amplify booms and busts.

There are better models for crafting balanced-budget amendments. One new approach has been proposed by Congressman Justin Amash (a Republican from Michigan) and has won some bipartisan support. His plan would essentially involve balancing the budget over the years of a business cycle. For instance, the proposal's rule constraining annual outlays (including changes in accrued net liabilities in entitlement programs, as noted above) to a level no greater than the average annual tax revenue of the previous three fiscal years would be far easier for Congress to adhere to. Congress could, with a three-fourths vote, override that constraint during wars or deep recessions. And instead of loading the amendment with additional mandates — like supermajority votes to raise taxes, supermajority votes to raise the debt, and so on — Amash's plan offers a simple, neutral rule with much broader appeal to lawmakers.

The main objection to such a "clean" amendment is that it could be used to force tax increases. But while a balanced-budget amendment would change the rules of the budget game, it would not fundamentally change the dynamics of public preferences. Significant tax increases would remain unpopular; meanwhile, a rule requiring balance would create enormous pressure for meaningful entitlement and spending reform that could help address the nation's fiscal imbalance.

Each of these rule changes would address some of the key drivers of our fiscal imbalance, and each would do so by taking not only economics but politics seriously — by helping to establish a structure in which the problem could be solved by rational democratic decision-makers.

KEEPING AMERICA STRONG

The clash over raising the debt limit that gripped Washington during the summer of 2011 was just the beginning, not the end, of our fiscal woes. The debate over the supercommittee and the House's rejection of a balanced-budget amendment during the fall of 2011 were likewise just the beginning, not the end, of the necessary battle over institutional reform.

We cannot know how even the early stages of this fight will unfold, but we can see where continued fiscal imbalance will ultimately lead. All great nations fall. And as economic historian Douglass North reminds us, they almost always fall when political institutions reveal their "inherent instability."

But history also shows us that adaptation is possible. Decline can be averted, at least for a time, by leaders who are able to see their way out of the trap of imbalance — out of the prisoners' dilemmas created by old rules that no longer suit a new set of circumstances.

We are in such a trap today. Everybody knows that our current fiscal practices are unsustainable. The question is whether our leaders will figure out in time just how we can escape that trap by rebalancing the rules of how we budget, tax, and spend.